‘Epicentre of white-hot passion’: 50 years of Donald Judd’s controversial concrete

In 1974, American artist Donald Judd sparked protests and raised eyebrows with an imposing concrete triangle. 50 years later, Judd’s Untitled has become a Minimalist masterpiece.

What would it take for art to get people to the barricades? The recent brouhaha concerning the dumping of selected Australian representative Khaled Sabsabi for the 2026 Venice Biennale has been a hot topic of debate in many corners of the art community. But as a news item in the context of a federal election and global financial meltdown it soon dropped off the front page.

The reality today is that art is shock-proof. Asking the public to accept a bicycle wheel as art or to put a two-million-dollar tag on a banana? As if, who cares. Peel another Banksy Beulah and see if anyone bids.

But within living memory there was a time when art was a touchstone of political dissent. That epicentre of white-hot political passion is still here: it’s at the back of the Art Gallery of South Australia, a concrete thing on the back lawn.

It’s titled Untitled, made on site in 1974, created by an American artist Don Judd, one of the landmark artists of the 20th century and whose Minimalist work revolutionised modern sculpture.

Looking at it today, 50 years later, it’s hard to imagine how something so minimal could arouse political passion. But in the early 1970s it represented for anti-Vietnam war activists an aspect of US ‘Coca-Colonization’, that had to be resisted at all costs.

The trigger point for local dissent was provided by a 1974 touring exhibition presented at the Art Gallery. Some Recent American Art, shot out all the lights with an uncompromising serve of American minimalism and industrial strength conceptual brutality. It included five plywood boxes by Don Judd, Carl Andre’s Lever (consisting of 137 firebricks arranged in a line), Dan Flavin’s fluorescent tubes installed in corners, and Joseph Kosuth’s text-only Art as Idea as Idea panels.

You might like

Donald Judd at 101 Spring Street, New York, 1972. Photo © Paul Katz / Supplied

There was quality venting by sections of the local academic and art community, who saw this exhibition as an example of ‘American imperialism’. A leaflet from the times declared, “All this is great and pernicious nonsense … It is no accident that a trite nihilism is now being peddled to us as ART. The last thing the great U.S.–dominated corporations want is a robust, popular art.”

Add to this volatility was the Australian Government’s purchase in the previous year of Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles — for $1.34 million!

Untitled was born in these testing times, flags and babies burning and hawks fighting with the doves. History records that Sydney’s loss was Adelaide’s gain. In association with the Some Recent American Art exhibition tour Judd accepted an invitation to travel to Australia and create a public work.

A suitable site could not be found near the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the opportunity was then offered to the Art Gallery of South Australia. From the artist’s perspective the commission held interest because he wanted to make outdoor works in concrete.

Donald Judd, born Excelsior Springs, Missouri 1928, died Manhattan, New York 1994, Elevation drawings for the sculpture ‘Untitled’, 1974, Adelaide, felt tip pen on paper, 20.9 x 29.6 cm (sheet); South Australian Government Grant 1974, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, © Donald Judd. ARS/Copyright Agency, 2025

Subscribe for updates

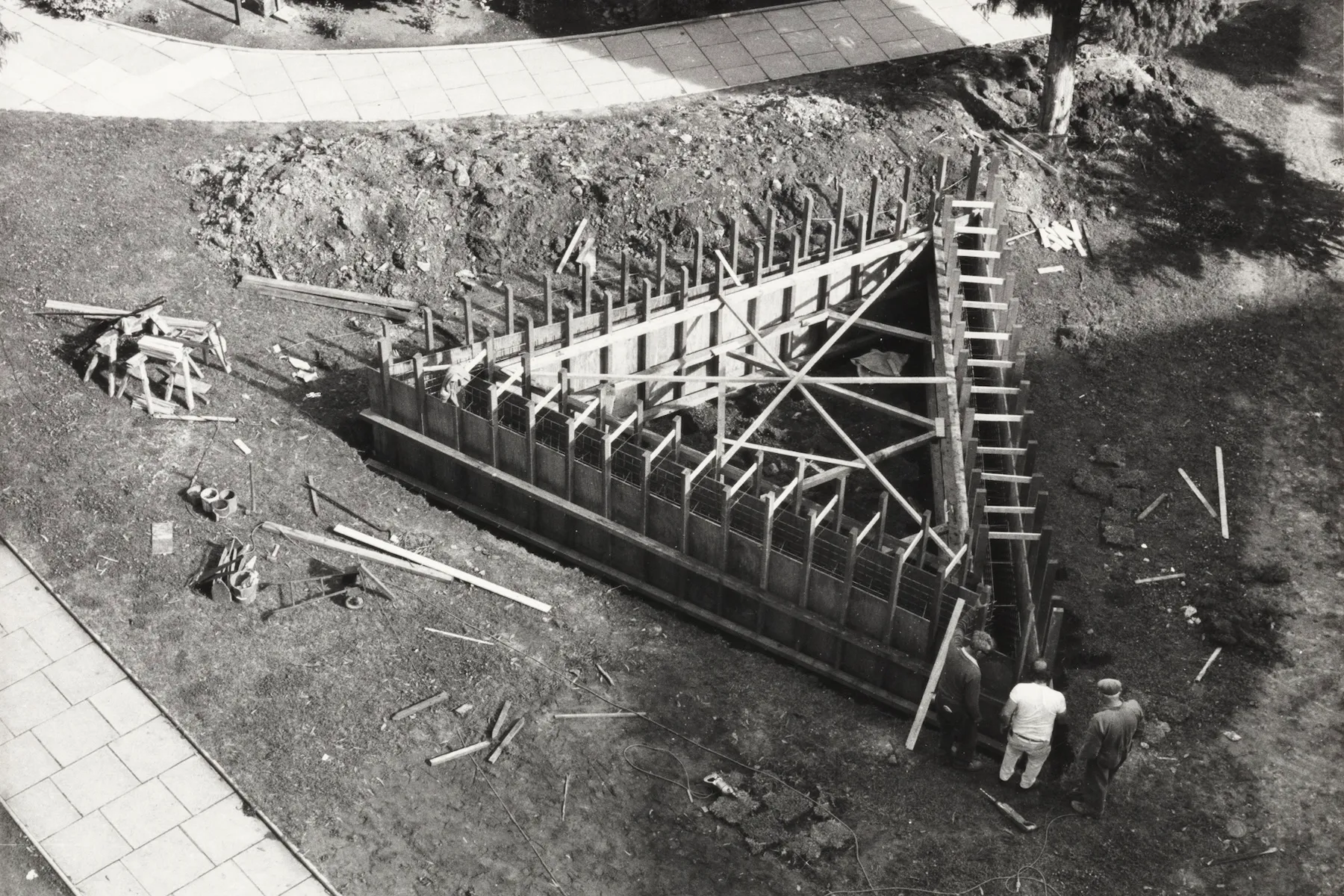

Judd arrived in Adelaide in May 1974 and commenced work on a permanent sculpture on a site at the rear of the Art Gallery. Some very minimal drawings, three pegs in the ground and the commission was underway.

The Art Gallery’s Untitled is one of the very few site-specific outdoor installations created by the artist. Others exist in Germany, New York and in the grounds of Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut (Judd’s first free-standing concrete sculpture). A feature shared between the Johnson Glass House and Adelaide’s ‘Judd’ is the beveled edge created by referencing the respective fall of the land on which each sculpture is sited. The Johnson work is circular, but the triangulation of the Adelaide work imparts a distinctive curvature that destabilises the formality of the symmetrical form.

Over the years the work settled into a life of relative obscurity, acting occasionally as a love nest for amorous couples, a temporary home for lost pets and a hiding place for naughty children. Curatorial staff wonder if many visitors are even aware of its art status. Not so the international Judd pilgrims who have the Adelaide work squarely on their checklist.

There was one notable event which temporarily shone a spotlight on the work. The Contemporary Art Centre of SA is marked its 70th birthday with a series of projects involving local artists creating temporary works in response to existing public art works and monuments within the city of Adelaide. George Popperwell, in responding to Donald Judd’s Untitled at the rear of the Gallery, installed a construction at the North Terrace entrance to the Gallery.

It consisted of a series of linked boxes on diagonally angled supports and set on a platform, placed hard up against the steps. Visitors to the Gallery needed to circumnavigate Popperwell’s work when entering or exiting. This construction had viewing holes set at various heights through which adults and children could peek. In doing they found themselves looking at some texts drawn from Judd’s writings and images including some sourced from original photographs taken of the construction of the Judd work in 1974. Perhaps there are some around Adelaide who can recall engaging with this work and can reflect on how or if it altered their perception of Judd’s work?

Donald Judd, born Excelsior Springs, Missouri 1928, died Manhattan, New York 1994, Untitled, 1974-75, Adelaide, reinforced concrete, 126.0 x 760.0 x 660.0 cm (irreg.); South Australian Government Grant in association with Marshall and Brougham Pty Ltd 1974, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Photo: Saul Steed, © Donald Judd. ARS/Copyright Agency 2025

As then and as now, this laconic work, despite the impressive claims made on its behalf by historian and curators, may continue to be an obdurate, uncompromising thing. The road to the deep north with Judd is to recognise his central philosophy which permeated his entire creative output.

The artist said, “I wanted work that didn’t involve incredible assumptions about everything … I didn’t want work that was general or universal in the usual sense. I didn’t want it to claim too much … A shape, a volume, a colour, a surface is something in itself.”

Art Gallery of South Australia curator Leigh Robb has, however, pointed out that one aspect of Untitled is the idea that the work is the sum total of object and the context in which it is located. So yes, it can aspire to be ground zero, be of itself and have no meaning beyond that. But yes, in referencing the ideal of the perfect horizon against the particular of the surrounding topography as it runs down to the river, it becomes an active participant in life around it.

No other public artwork in Adelaide comes as close to stripping the contradictions within the ‘what is art’ question to the bone.

The Art Gallery of South Australia will mark the 50th anniversary of Untitled at its next First Fridays event on May 2 with guided tours, public talks, and the screening of a new documentary about the work.

A public display curated by Maria Zagala, Curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs, will be open in Gallery 17.