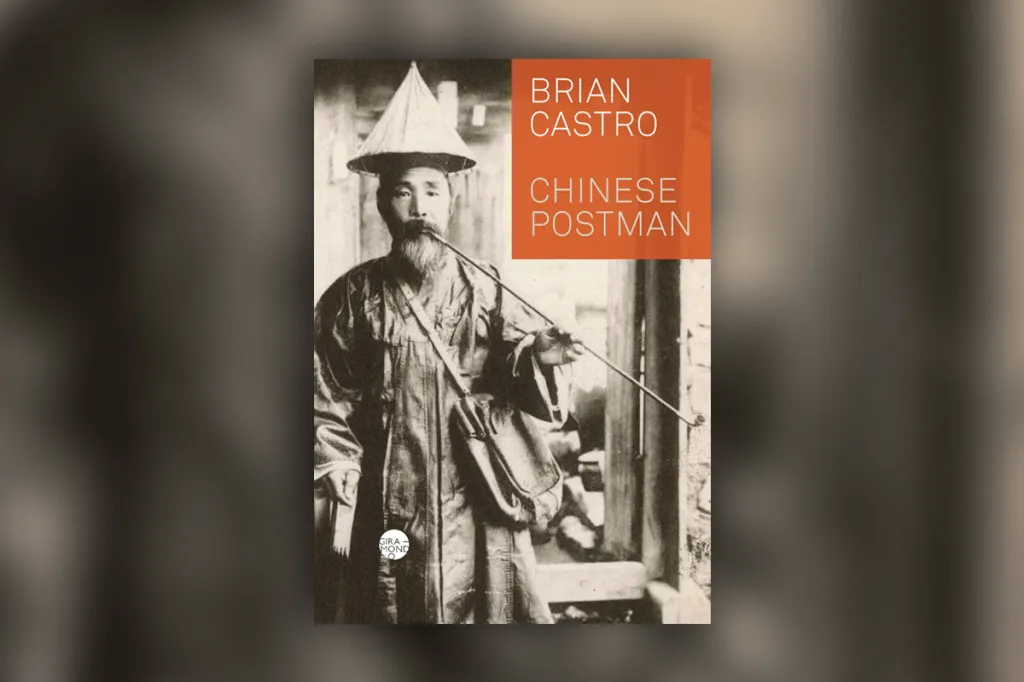

Book review: Chinese Postman

In his eleventh novel Brian Castro makes serious use of the adage ‘write what you know’, expertly melding autobiography and fiction in a literary treatise on aging, memory and a life well lived.

Brain Castro is one of Australia’s most awarded and revered writers, well-known for his risk-taking and stylistic storytelling. In Chinese Postman, as well as in previous books, Castro gifts his readers a protagonist who is part creation, part author. By this I don’t mean that he lends parts of his history and attributes to his characters — most writers do that. Rather, Castro emboldens and celebrates who he is beyond the page, and doesn’t aim to disguise it within the work.

In Chinese Postman we meet Abraham Quin, a migrant in his mid-seventies, retired from academia and living in the Adelaide Hills. Castro, too, is a migrant in his mid-seventies. A retired Chair of Creative Writing at the University of Adelaide, he also resides in the Adelaide Hills. If you knew the author, you’d pick out plenty of him in the character of Quin, from where he sits down to write, to the veneration he feels for his dogs. Though it turns out to be a lot of fun playing spot-the-author, and though the author swaps from a third-person ‘he’ to a first-person ‘I’ seemingly willy nilly, this is far from a gimmick. It’s a loosening of identity — or perhaps a strengthening of identity — where Castro both holds himself up for inspection and raises the stakes.

Quin lives a lonely life, no longer working or keeping in touch with friends, and his third and last wife has died, his favourite dog as well. Though he’s fit enough to cycle for both transport and leisure, he feels old and stooped in his bones. He’s memory-laden and worries about forgetting. He’s melancholic, willing to submit to whatever ending he believes has already begun. Indeed, he’s grieving.

“We cry at night and are brave in the mornings,” reads an email sent to Quin by a woman named Iryna. Professing to be a fan of his books, Iryna says she lives in Ukraine and cares for her child and dozens of others while her husband is incommunicado, fighting Russian soldiers.

You might like

The words are a reality of war for Iryna, while they’re a metaphor for Quin’s feelings about his late stage in life. But through their ongoing exchange of letters and emails, Quin finds purpose and momentum. As readers, we see this in the richness and abundance of the very minutia of Quin’s/Castro’s memory, reflections that take on a type of energy one might consider joyful, regardless of whatever downhearted topic it was that got the protagonist / author rolling.

Quin sends Iryna money, wants to sponsor her and her daughter and mother to come to Australia and stay at his house with him, which he renovates in readiness for their arrival. But is Iryna who she says she is? Is Quin being catfished? Does it even matter to him in the end?

There are no chapters in Chinese Postman — in fact the story progresses through a series of very small sections or fragments. Open the book to any random page and you’ll find that the style proves aesthetically beautiful and clean, but more than that, the structure mimics memory itself. One image slides into the next, despite the images initially being unconnected. It’s as if Castro is telling us from a place of newfangled discovery, Look what a life is! Isn’t it glorious!

Chinese Postman, by Brian Castro, is published by Giramondo