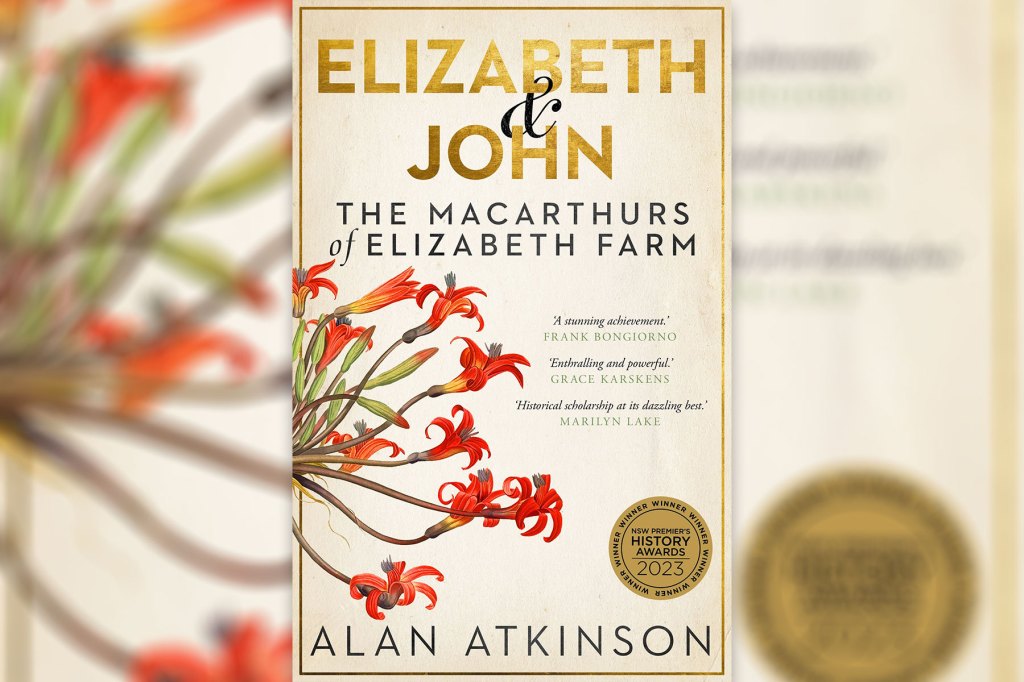

Meet the Macarthurs – Australia’s first power couple

John and Elizabeth Macarthur were Australia’s first power couple and the lives of this dynamic duo are beautifully explored in a compelling new release.

Astrologers should thank their lucky stars for Australia’s first power couple – the Macarthurs.

Born a day apart in August 1766, their differences were complementary: he combatively self-righteous – the protagonist of three duels in the so-called Age of Reason; she bright as a button, inquisitive about the world and, if anything, his superior when it came to business. Theirs was a union fated for success.

As books about consequential figures from history proliferate, it is becoming increasingly difficult to categorise them – even more so in the specialised field of joint biography, where added to the problems of writing from inside their subjects’ worlds (and heads) is the difficulty of accurately estimating the contribution made by each member of the partnership. The late Hazel Rowley’s landmark study of the Roosevelts (Franklin & Eleanor) masters this challenge as does T. Ryle Dwyer’s double study of Michael Collins and Eamon de Valera, Big Fellow, Long Fellow.

Distinguished Australian academic Alan Atkinson has also achieved success in this paperback edition of his dual biography (first released as a hardback in 2022) which – recurring to my point about mutable categories – is equally a work of history, psychology, politics and cultural studies.

At his most insightful, Atkinson is brilliantly reductive – as with the most fateful disagreement of the couple’s lives – over whether John should return to the remote colony of New South Wales after seven years back in England or whether his wife would submit to his wishes.

You might like

In passages highlighting the risk that “the family would be permanently split between two hemispheres”, he lists the lures of London that outweighed an Australian destiny. In John’s mind, “its concentration of power, clever and powerful friends, to watch the achievements of all four sons, the pride of his life”.

And then, in a single illuminating line, he explains the ultimate decision to base their future 17,000km away from London by reference to their respective backgrounds: “The cloth-dealer’s son argued with the farmer’s daughter.”

The basis of their future income lay in farming. John’s lifelong interest in fabrics was also relevant, as befits the founder of the Australian wool industry, the staple of the country’s prosperity for a full century and a half. Still, another Macarthur specialist, Michelle Scott Tucker, has argued it was Elizabeth who established the industry while her husband took all the credit.

Atkinson’s work, while acknowledging the patriarchal world they inhabited, stands as a mild corrective to that view. Unstinting in his praise of Elizabeth, he demonstrates that, in their happiest years together, each was essential to the other’s mission in life.

Subscribe for updates

Or, put more simply, love was the force that drew them together and drove them on.

Over almost 500 pages the professor sustains a kind of literary high-wire act, based on a method that sometimes relies inescapably on guesswork. Over five pages in Chapter 27, Variegated Truths, he falters with a series of meditative paragraphs beginning: “Am I just?”, once varied to “Am I not just?” These longueurs – an attempt at interiority descending from plausible surmise to pure speculation – form the weakest part of an otherwise impressive tale.

Better than most of the standard works on early colonial history, Atkinson conveys the mixed motives that actuated the Macarthurs. We see the Calvinist in John – a military officer with a strict sense of honour – goad successive colonial governors into branding him a troublemaker. Philip Gidley King had him arrested following his second duel and demanded a court-martial, to be held in London. “As the jokers put it, John Macarthur was to be ‘transported to England’,” writes Atkinson.

While both were products of a society steeped in the concept of Christian virtues, they were also children of the Enlightenment. Having joined the colony-rescuing Second Fleet and taken up a 100-acre (40ha) land grant at Parramatta, Elizabeth busied herself studying – music, the stars, algebra and botany. She wrote to an English friend: “Since I have had the powers of reason and reflection, I never was more sincerely happy than at this time.”

Bringing up their children single-handed as John tried to secure stable sources of funding on the other side of the world, it was Elizabeth who made the farm named after her a going concern. Until 1812, when he received assurances regarding the future supply of fine wool, the farm’s main income source was mutton, and she became the first NSW settler to make hay for sale.

The ambivalent relations between the Macarthurs and the country’s original inhabitants are skilfully depicted in this work. Up on the Hawkesbury, Macarthur played a part in the 1795 massacre known as the Battle of Richmond Hill – part of the warfare triggered by invasion (and the author isn’t shy about calling it that). Yet he and Elizabeth always cultivated the friendship of the Burramattagal people nearer to their Parramatta) home, and Atkinson makes it clear that Tjedboro, the Dharug man who came to live with them, was not kidnapped but did so enthusiastically.

The “house guests” who robbed them before absconding were Irishmen, who became among the first practitioners of two pursuits new to Australia – cattle duffing and bushranging.

Atkinson evokes the full gamut of emotions that governed the Macarthurs’ adventurous life, from the joys of communion, intellectual stimulation and productive enterprise to the sorrow of permanent parting (Elizabeth never again set eyes on their son John after he returned to England at age seven).

At no point – not even when recounting their approaching deaths – does the pathos reach a higher pitch than in the pages where John’s mental collapse, retrospectively diagnosed as a bipolar disorder, is recorded, and he is declared insane.

Once again, Atkinson’s extraordinary, almost poetic, ability to sum up a world of emotions in one perceptive line comes to the fore. Elizabeth, in the closing chapter of her life, he tells us, was “alone at open sea”.

Elizabeth & John: The Macarthurs of Elizabeth Farm by Alan Atkinson, UNSW Press, $34.99