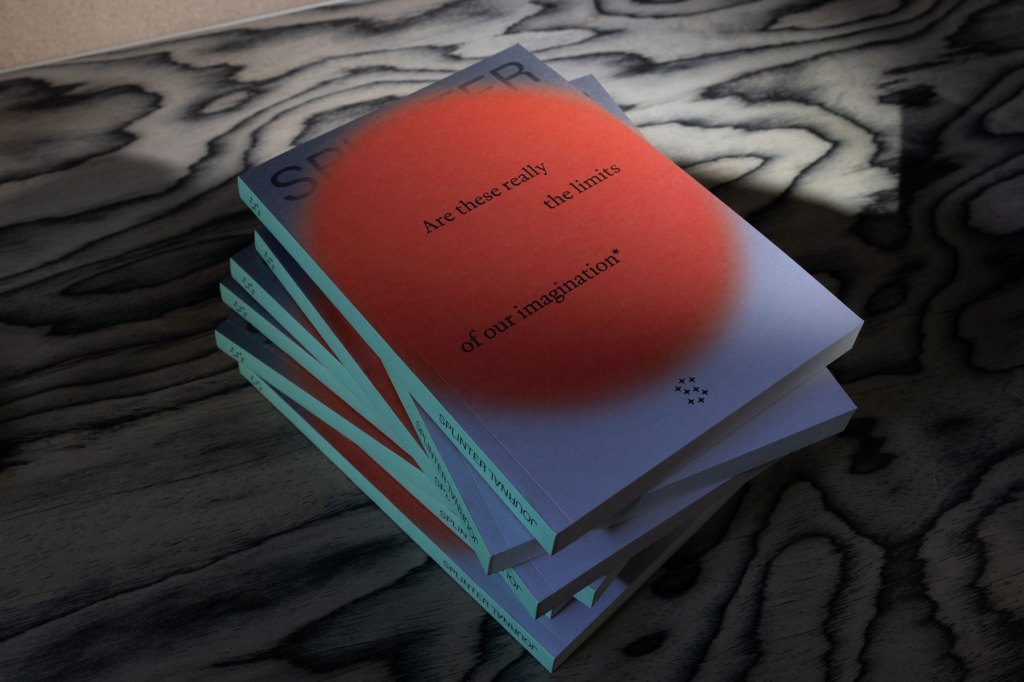

Reality bites: Splinter literary journal releases its first issue

South Australia’s first print literary journal since 2012 features work by 25 writers from around the world – including seven from SA. Its editor, Farrin Foster, reveals what readers can expect from the issue released this week.

As the editor of new literary journal Splinter, I launched our writer callout earlier this year with a huge amount of trepidation. The journal had only just been given a name, its website had been live for about four seconds, and I think most of the people following us on social media were related to me.

I was concerned that not enough writers would see the callout, let alone want to submit.

Somehow, though, probably through the dense web of connections that exist in the writing community, submissions began to flow in. Every day, I was delighted to see (often) dozens more arrive. When we started receiving poetry from Nigeria, memoir from Canada, and fiction from India, I began to truly relax.

In the end, there were hundreds and hundreds of pieces, all of an alarmingly high quality. The process of winnowing them down was very, very difficult. I worked with a group of 11 emerging to mid-career writers and editors to assess every submission and we came up with a shortlist that was far from short.

We’d asked writers to engage with the slipperiness of reality in their work, but amid that overarching theme, writers seemed to have naturally fallen into a few sub-categories.

You might like

From Tasmania, author and editor of Island magazine Jane Rawson sent us an introspective, funny, and illuminating essay on sonic environmental destruction, which was part of a thoughtful tranche of submissions that examined the often-artificial divide between human and animal experiences.

Apocalyptic fiction was – of course, given the state of the world – another prevalent trend, and many of the most chilling pieces in this genre felt as if they barely diverged from the here and now. From this group, our final choices for Splinter include an absurd and extreme story from Sydney writer Frank Marrazza that manages to bring gun control, the distressing influence of online platforms, and some light cannibalism all into one wildly pacey piece.

Another standout theme was identity. Among the submissions, there were dozens of eloquent, striking moments of writers and characters prodding at the barrier between the self and the world, asking whether there is any stable inner core that remains protected from the chaos of change. What happens when we become parents, become employees, receive a diagnosis, shift our gender, or our memories begin to blur – have we completely changed? Or is there some part of us that remains untouched?

Among the most electrifying of these pieces is a relatable but shockingly insightful poem from the lauded Jill Jones, and a form-bending memoir piece from SA writer Ryan J Morrison, who slips between fragmented recollections and informative tangents to somehow build a highly-affecting picture of his search to pin down a sense of self. Miles Franklin-shortlisted writer Hossein Asgari also took on this theme with a gentle fictional approach, in which his protagonist shepherds his father through dementia with the help of beautiful communal touchpoints.

Subscribe for updates

Splinter editor Farrin Foster. Photo: Jessica Clark

As we started braiding these threads into a publication, we also wanted to look more directly at the reality of the current moment, which we leaned into with a series of essays and criticism pieces.

Writer, activist and human rights lawyer Sara M Saleh authored a searing indictment of international law’s failure in Gaza, detailing how the lack of protection offered to Palestinians reflects systemic and cataclysmic flaws in the system.

Karen Wyld, drawing on deep research she’d done for her Masters, deconstructed Euro-centric literary misreadings of writing by First Nations and other Global South authors, arguing that critics and publishers often misidentify magic realism because of their cultural bias around definitions of “magic” and “reality”.

And, because no publication is complete without the sport pages, Sam Elkin takes us inside the AFL’s response to the science on repeated concussions, questioning how it might be affected by our national tendency to equate brutality with bravery.

For balance and because reality, as well as being quite horrifying, is also often comedic and wonderful, there are lots of funny bits and a surprising amount of sex in Splinter, too (although some of the sex, as examined by critic Susie Anderson, is too literary to be all that good).

This week, the journal finally arrives back from the printers – ready to head out to our subscribers and to bookstores. At 192 pages, it is designed to sit on a bedside or coffee table and be read for the full six months between issues.

Making Splinter has felt like taking a tour of the self and the world; it has been exhausting, but also a funny, revealing, and genuinely insightful process. I really hope that reading it feels similar, although perhaps without the sense of exhaustion.

Splinter’s first issue is available via the journal’s website and in selected bookstores.