Diary of a Book Addict: What is normal?

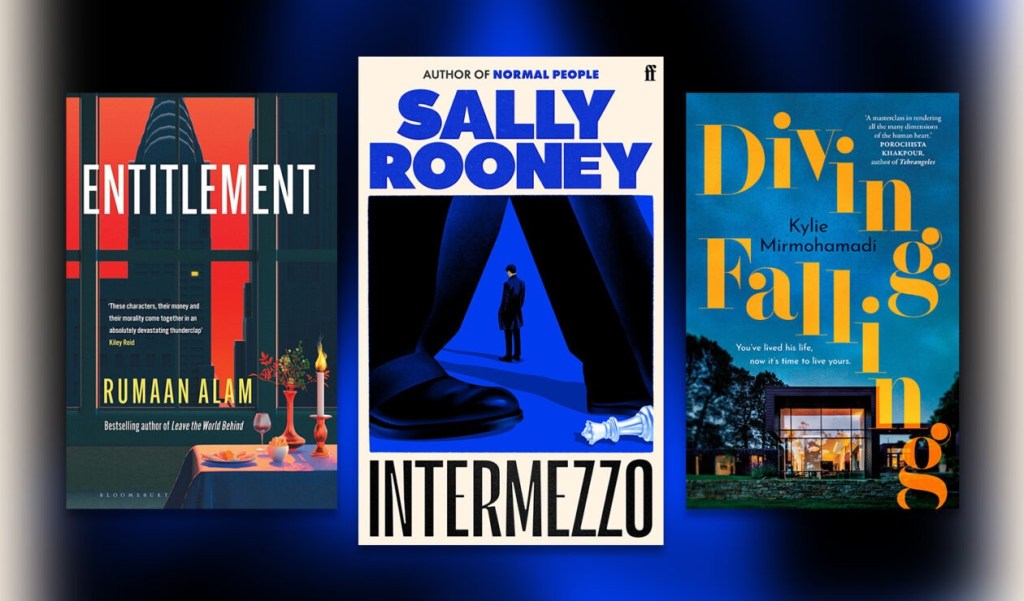

This month our columnist shares her thoughts on the latest book from bestselling author Sally Rooney and two other new novels – one she loved and the other she wishes she’d left on the shelf.

People have strong opinions about Sally Rooney, whose fourth novel, Intermezzo (Faber), hit shops worldwide last week. Her second novel, Normal People, and its streaming adaptation made her a cultural phenomenon: the reluctant queen of sad-girl-lit. Her third was published amid a torrent of love and hate, which often seemed more about making cultural noise than about Rooney or her books.

When I read Normal People a month before it was published in 2018, I was blessedly free of expectations (apart from having enjoyed her debut, Conversations with Friends). I loved the book as a forensically sharp romantic comedy about overthinking misfits (hyperarticulate Marianne and taciturn Connell) who commune at an almost cellular level, but are kept from each other through miscommunications grounded in social context.

I relished the dance between surfaces and spoken dialogue – how the characters performed themselves – and internal dialogue, driven by insecurities and desire. I admired how Rooney anchored it all in family and social dynamics, how she considered the role of class and money. Like so many, I was hooked on the push-pull love story, but I was also interested in the hidden social mechanics the novel revealed.

Rooney’s third novel, Beautiful World, Where Are You?, which explored the love lives of best friends, a literary magazine editor and a shockingly successful young novelist, seemed to suffer from second-novel syndrome. It was narrated from a god’s-eye view, at a distance from the characters, and the long emails within the text only heightened this sense of being told about the action, rather than inhabiting it.

It felt like, in the wake of her success, Rooney needed distance from her readers, even while taking that success as a subject. It also felt like, in moving away from the intimate inhabitation of her characters she performed so well and introducing the epistolary element, she was trying new things to prove she wasn’t repeating herself. It was my least favourite of her novels.

“I am really interested in what’s considered ‘normal’,” Rooney told an audience at London’s Southbank Centre last week. And indeed, the joke of Normal People’s title is that neither Marianne nor Connell feel “normal”: both are desperately trying to perform what passes for normality according to the social environments they inhabit.

Intermezzo feels very different again from Rooney’s previous work, in many ways. First, it’s a longer, denser novel than we’re used to from her. Second, it (mostly) moves away from college students and literary workers. Third, it centres two brothers, rather than the young women she’s most celebrated for (though of course she’s written male narrators before). Ivan and Peter have just lost their father to cancer. The novel opens with 32-year-old Peter leaving the funeral, reflecting on 22-year-old Ivan’s discomfort and ugly second-hand suit, and on his own comparative “social brilliance”.

Intermezzo feels very different again from Rooney’s previous work, in many ways. First, it’s a longer, denser novel than we’re used to from her. Second, it (mostly) moves away from college students and literary workers. Third, it centres two brothers, rather than the young women she’s most celebrated for (though of course she’s written male narrators before). Ivan and Peter have just lost their father to cancer. The novel opens with 32-year-old Peter leaving the funeral, reflecting on 22-year-old Ivan’s discomfort and ugly second-hand suit, and on his own comparative “social brilliance”.

You might like

A human rights lawyer and (like Rooney) a former debating champion, Peter is involved with two women. He sleeps with Naomi, 22, a beautiful college student who lives in a squat and is “borderline what you might call a sex worker”. And he has a romantic but sexless “platonic life partnership” with his ex-girlfriend and soulmate, Sylvia, who was injured in an accident in a way that makes sex impossible. Peter is drawn to both women, who know about each other’s place in his life, but tortures himself about how to make a choice neither are demanding of him.

Younger brother Ivan is first introduced to us through Peter, who describes him to Naomi as “a complete oddball” who is “kind of autistic” and “a chess genius”. As an autistic reader, I recoiled at the way Ivan was talked about by Peter and his mother, and at first honestly wondered if I could stick with this novel. But then we meet Ivan from his own perspective, as he takes part in a chess event at a small-town arts centre and meets Margaret, its attractive 36-year-old program director. Ivan berates himself (and apologises to Margaret) for talking too much about chess, but he’s also kind, thoughtful and intelligent. “It’s always interesting to hear people talk about things they’re passionate about,” Margaret says, and means it.

It’s not giving anything away to tell you this meet-cute becomes a one-night stand and more – and quickly forms the central love story of the novel, progressing in a more or less linear fashion, albeit with obstacles, parallel to the jagged roundabout of Peter’s relationship woes. The most meaningful will-they-won’t-they of Intermezzo, though, is not the romantic relationships, but the one between the two brothers, who alternate between family echoes and memories of childhood closeness, and present-day judgments, resentments, rifts and moments of connection. Will grief bring them together or drive them more definitively apart?

As I read, my relationship to the novel changed. I became more sympathetic to Peter, who I initially loathed. His narrative of success and “normality” is revealed as a thin shield against an internal struggle, including deep grief for the loss of his simple past happiness with Sylvia. That sadness is now entangled with grief for the father he wished he was closer to.

And while Ivan struggles, too, with loneliness, navigating “impenetrable systems” and a lifetime of being misunderstood alongside his grief, Rooney hasn’t written him as the stereotypical autistic loner we first perceive through his family’s eyes. He has a network of friends, including in the chess community, and his candid vulnerability with Margaret has an emotional intelligence his brother’s relationships often lack.

This is where Rooney’s interest in inviting us to question “normal” is once again clear. As her novel unfolds, characters who define themselves by fitting social conventions are invited to ask whether their best chance of a genuinely satisfying life might lay outside them. The blank equilibrium of so-called niceness, too, is challenged. “It’s difficult,” says one character, “when you’ve been through certain things, and people in your life don’t necessarily believe you. Or they just don’t want to know.”

This is just part of Intermezzo’s deeply moving exploration of the complexities of families – particularly the tension between expectations and accepting each other as we are. Accepting imperfection, valuing effort and sitting with discomfort. As in the best novels, it emerges that there are no straight-up villains or heroes. I surprised myself with tears at small, unexpected moments.

Questions of the good life, or how to be good, have long been a preoccupation of novelists. Rooney seems to suggest achieving these things lies in genuinely asking these questions, rather than holding fast to definitive answers.

Subscribe for updates

Intermezzo represents both a return to the confidence of Rooney’s first two novels and a genuine progression of her craft and scope as a novelist. It plays to her strengths, in its deep inhabitation of her characters and canny dissection of “normal”, while showing she can stretch herself beyond worlds she’s inhabited and successfully play with form and perspective.

Australian novelist Kylie Mirmohamadi’s Diving, Falling (Scribe) is an absolutely immersive art-world family drama, just crying out to be adapted by John Edwards (Love My Way, Tangle) for a streaming series. Like Intermezzo, it opens with the aftermath of a funeral: of internationally famous Melbourne artist Ken Black. He leaves behind Leila, the novelist wife who helped burnish his legend, a longtime mistress (Anita, the photographer wife of his best friend and art dealer) and two sons, immortalised in one of his most famous paintings.

Australian novelist Kylie Mirmohamadi’s Diving, Falling (Scribe) is an absolutely immersive art-world family drama, just crying out to be adapted by John Edwards (Love My Way, Tangle) for a streaming series. Like Intermezzo, it opens with the aftermath of a funeral: of internationally famous Melbourne artist Ken Black. He leaves behind Leila, the novelist wife who helped burnish his legend, a longtime mistress (Anita, the photographer wife of his best friend and art dealer) and two sons, immortalised in one of his most famous paintings.

“He had told me once, when he first started painting our children, that he put them together so he could take them apart,” Leila reflects. An old press photograph of her and Ken is captioned: “Melbourne art world’s smiling assassin, and his literary accomplice.” This, she says, is particularly insightful.

Ken is, as Claire Dederer would say, an art monster, a control freak who enjoyed being rewarded for bad behaviour and terrorised his sons, particularly the one he saw himself in, who was his favourite. Leila, who loved him, has always believed she protected her sons. But, she’s forced to ask: Did she? This is just one of the ways Mirmohamadi asks us to think about complicity. Another way is when narrator Leila, assumed by her sons to be a victim, casually admits she knew about her husband’s affairs, including Anita, who he left $69,000 in his will.

Leila’s upset less by the infidelity than by her control over Ken’s legacy being usurped, first when Anita convinces her sons, executors of his artistic estate, to let her photograph and exhibit his work – and later, in a series of ways. Another challenge is the beautiful, controlling daughter of her best friend, an emerging gallery curator, who reignites a romance with her son after he becomes his father’s executor. “You’re not the head of a mafia clan,” one son tells her.

Diving, Falling is another woman-in-midlife-crisis novel, joining Miranda July’s All Fours and Emily Perkins’ Lioness in depicting a woman in her forties or fifties who has structured her life around serving others rather than prioritising her own desires. Mirmohamadi has created a vivid, alternately alluring and repelling world, beautifully detailed with artwork, architecture and intricately imagined relationships. I can’t remember a recent novel I’ve more thoroughly enjoyed.

Diving, Falling drips with money, in a way that feels unlimited – paintings sell for millions, a capacious Sydney property with beach views is bought as a fancy, the marital house on the Yarra is “a brutalist castle” and “Australia’s Fallingwater”. Entitlement (Bloomsbury), by Rumaan Alam – author of the bestselling, Netflix-adapted end-of-the-world novel Leave the World Behind – takes money as its subject. Set in New York City during the Obama years, it follows Brooke, a young Black woman with a white activist lawyer mother, who is transformed while working for a foundation set up by a paper industry billionaire.

Diving, Falling drips with money, in a way that feels unlimited – paintings sell for millions, a capacious Sydney property with beach views is bought as a fancy, the marital house on the Yarra is “a brutalist castle” and “Australia’s Fallingwater”. Entitlement (Bloomsbury), by Rumaan Alam – author of the bestselling, Netflix-adapted end-of-the-world novel Leave the World Behind – takes money as its subject. Set in New York City during the Obama years, it follows Brooke, a young Black woman with a white activist lawyer mother, who is transformed while working for a foundation set up by a paper industry billionaire.

I was intrigued by the premise for this novel, and the interviews I’d heard with the author, who said the original idea for the novel was a person falling in love with an apartment. This persists in Entitlement when Brooke, an art history graduate from a good college with no real ambitions beyond a vague desire to do good, is seduced by the ambitious worldview of her new boss, billionaire Asher Jaffee, and becomes obsessed with the idea of buying a modest Manhattan apartment as self-realisation.

“Demand something from the world,” Jaffee advises her, being a mentor without thinking about how facile his advice is, or how particularly it’s worked for him. Later: “if you don’t ask for what you’re owed, who can you blame if you fail to get it?”

The driving force of the novel is the question of what Brooke will do to get what she’s “owed”. Soon, she’s taking Jaffee at his word, combining magical thinking with using the corporate credit card inappropriately and overpromising on behalf of the foundation. Brooke firmly believes herself to be a good person. She also increasingly believes in her own disadvantage, due to her job but also to watching her childhood best friend, who has just come into an inheritance, pay cash for a two-bedroom apartment in the West Village.

Honestly, I was very keen to read this book, but had to push myself to finish it. I did because I wanted to know what would happen. But I was annoyed by Alam’s over-telegraphing of the book’s themes and subtext, and the thinness of his characterisation. Nearly halfway through the novel, Brooke’s friend observes of her: “She was different. New job, new you.” Jaffee reflects that an assistant is “more loyal than any of his three dogs”, which seems like something a person who believes himself to be good might subconsciously believe, but is unlikely to articulate. After the death of Brooke’s mother’s close friend, a character says, “Maybe Paige’s dying is making you think about yourself, living. That’s natural” – although the events of the novel clearly make this connection for us, without needing to spell it out. I could go on. It’s as if Alam believes his readers are extremely thick.

I’ll watch the Netflix adaptation when it comes out, but I regret the time wasted reading the novel, which seems like a template for the screenplay. Don’t necessarily listen to me, though: nearly all the many other reviews are positive.

Jo Case is a monthly columnist for InReview and deputy editor, books & ideas, at The Conversation. She is former bookseller at Imprints on Hindley Street and former associate publisher of Wakefield Press.