Why SA’s First Nations Voice has had a bumpy start

Resignations, competing priorities, small budgets and high expectations: the first year of South Australia’s First Nations Voice hasn’t been easy. But Aboriginal leaders have reason for optimism, too.

On March 26, 2023, thousands of people gathered on a rainy day outside Parliament House to watch South Australia become the first state to establish a First Nations Voice to Parliament.

The ceremony came at a time of great optimism in Aboriginal affairs; polling still showed majority support for enshrining an Indigenous Voice in the Australian Constitution, and the Malinauskas Government hoped success for the State Voice would boost support for the federal referendum.

Premier Peter Malinauskas told the crowd on that overcast Sunday that “there are no more powerful deeds than South Australia becoming the first place in our nation to pass a law enshrining an Indigenous Voice to our parliament”.

But there are risks to being first as well.

In the 628 days since that special parliamentary sitting, the government has had to postpone the inaugural Voice elections then face criticism for low voter turnout. Three elected Voice members – including one of its most senior leaders – have resigned, as has the organisation’s chief staff member. Meanwhile, other representatives have publicly expressed frustration about the Voice’s structure and resourcing.

All of this after 64 per cent of South Australian voters said “No” to the federal Voice. The result devastated the Voice’s elected members but emboldened the model’s critics, with Liberal Party leader Vincent Tarzia already signalling he as Premier would repeal the Voice “if it does not achieve the outcomes that it sets out to”.

The heightened scrutiny is not lost on State Voice presiding member Leeroy Bilney, who spoke directly to Tarzia and the rest of state parliament in a historic inaugural address last month.

“There’s a lot of cynicism around the creation of the Voice,” Bilney told MPs.

“And there’s a heavy burden on us to prove ourselves, to prove ourselves to First Nations people who heard about the Voice and thought, ‘hmm, been there, done that’ and think we’re just going to be another failed advisory that has been established to make it look like something is being done without ever achieving anything.”

So, what has the Voice achieved so far? And is it set up for success?

Starting from scratch

Ngarrindjeri woman Deb Moyle works at the grassroots.

She leads Tiraapendi Wodli, Kaurna for “Protecting Home”, an Aboriginal community-led organisation based in Port Adelaide that coordinates counselling, psychology, Centrelink and drug and alcohol services. Their office on Dale Street, according to Moyle, handles more than 500 people a month.

“At Tiraapendi Wodli, we have a lot of Aboriginal people sitting at the front of our building; we’ve got some chairs there that community are welcome to sit and have a cup of tea,” she said.

“There’s not a day that goes by that I [don’t] get somebody driving by, beeps their horn and tells me that they voted no.

“They take it out of their time to tell a group of Aboriginal people that they voted no – how does that make an Aboriginal person feel?”

Moyle was one of 41 candidates to stand for the Central region at the inaugural Voice elections in March. She was elected with 65 first preference votes, equating to 5.8 per cent of the 1130 formal ballots cast.

With more than 20 years’ experience as a public servant, including as principal policy officer at the old Department for Education and Early Childhood, Moyle knows her way around government. She also knows that not everyone on the Voice has the same experience.

“This Voice has brought us inside the room. We’re sitting at the table, but we’re also learning how to navigate government systems,” she said.

“Government systems are quite complex. Legislation and policies are complex, and they’re layered.”

Asked how the Voice was progressing, she said: “It’s slow because it has to be slow.”

“We are an adviser to government, that’s all we are, and that means there’s a lot of work that’s happening in the back shop,” she said.

“Because you’re actually asking a group of Aboriginal people to come into government and know what the heck is going on, so it’s going to take a bit of learning for us.”

‘We are not groomed politicians’

Forty-six Aboriginal people were elected across the six Local Voice regions in March. The Central Voice represents metropolitan Adelaide and has more elected members (11) than the regional Voices (7) to account for its greater population.

The Central Voice has held three meetings this year and nominated two presiding members – Douglas Clinch and Susan Dixon – to sit on the State Voice, the overarching 12-member body that meets with state cabinet and department CEOs and can speak to parliament on bills of interest.

This local-state structure, and a requirement that each of the Local Voices must meet between four and six times every year, was established by legislation. Each Local Voice was also given a code of conduct and member induction guide.

But the Voices were left to determine other elements from scratch, including their meeting procedures, terms of reference and governance structures. Bilney told parliament it’s been like “building the plane and flying it at the same time”.

“We are not groomed politicians,” he told reporters after his inaugural address.

“We don’t come with that already existing knowledge, and so for a lot of us, it’s like, basically, we just dive straight in.

“Understanding that world is what we’re still yet getting our head around.”

The quarterly meeting schedule means items for discussion pile up; all three Central Voice meetings have had a “packed agenda” and lasted a full day, Moyle said, with debate focused on “positioning ourselves about what we’re good at”.

‘This Voice has brought us inside the room… but we’re also learning how to navigate government systems’

But the Central Voice, like the five other local Voices, is yet to formalise its list of priorities for the State Voice. Bilney said this is expected to happen in 2025, and Moyle believes it’s something that needs attention.

“It’s going to take more than three meetings… we think we’re nearly there but it’s not going to happen overnight,” she said.

“And everyone’s saying, ‘Well, the Voice should have fixed something, or the Voice should have done this for them’, and I’m going ‘No, not really’.

“We’re just figuring out our own identity, because everyone else is telling us what we should be doing.”

A juggling act

The Central Voice made headlines on November 14 when it was revealed that two of its members, Tahlia Wanganeen and Cheryl Axleby, had resigned only months after their election.

Two other local voice members, Darryle Barnes and Joy Makepeace, from the Riverland & South East and Yorke & Mid North regions respectively, also pulled the pin, although Makepeace has since decided to stay on.

The Electoral Commission says it will hold supplementary elections to determine their replacements.

Wanganeen’s resignation was particularly significant given she was chosen alongside Bilney to be a State Voice presiding member. InDaily could not reach Wanganeen for comment, but she told the ABC last month that the current Voice model is “unsustainable” and that “everybody has day-to-day jobs that they need to perform”.

Balancing full-time work with Voice commitments – particularly meetings that last a full day – was the most common issued raised among elected members InDaily spoke to over the last two weeks.

The problem is particularly acute for regional Voice members, who make long journeys across the state to attend official meetings and community engagements.

“I was shocked when I read about the resignations, but I can’t say that I was surprised,” said Dharma Ducasse-Singer, a member of the Far North Local Voice, who described the Voice’s opening months as “bumpy”.

“Everybody has different lives and that’s one thing that the media has to recognise.

“There are problems with the structure – it is hard to be in this as an everyday person, and if people feel that they can no longer commit, or other opportunities come up, to me that’s understandable.”

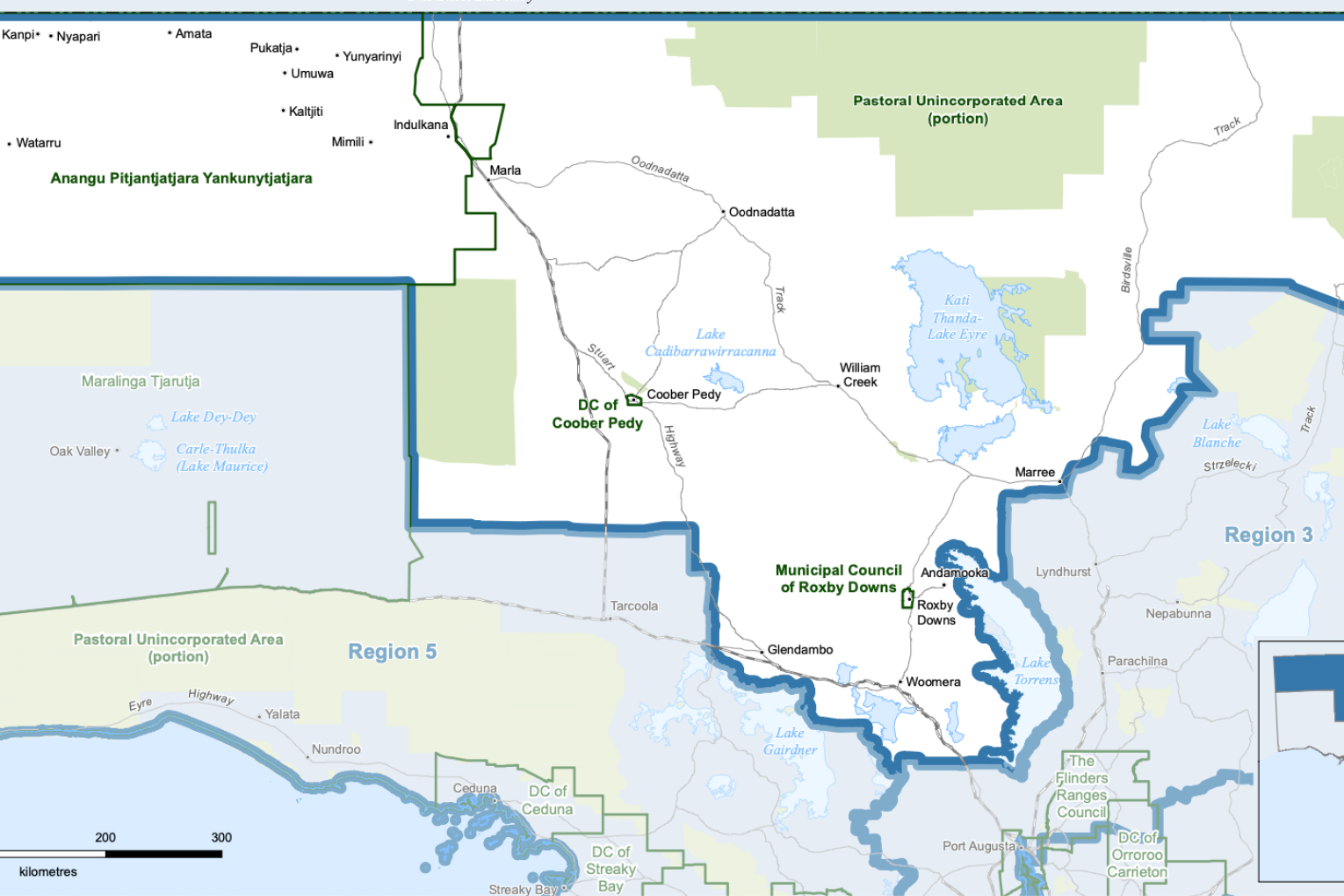

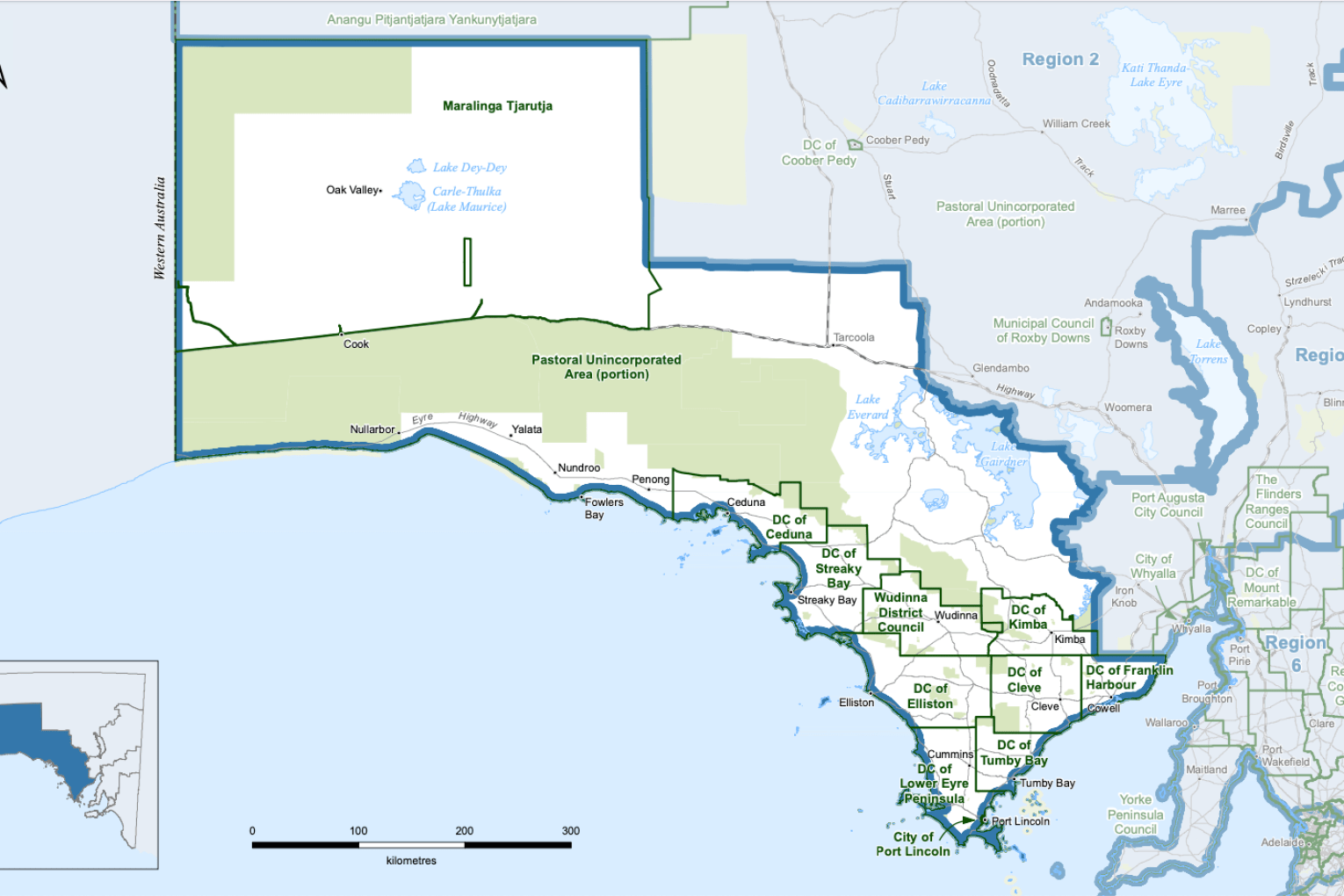

Ducasse-Singer is a Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara woman representing a region that stretches the length of the state from the APY Lands to Innamincka. It also incorporates Coober Pedy, Roxby Downs and Woomera.

She is currently living in Adelaide studying at the University of South Australia and says this makes her “one of the lucky ones”. She uses her study breaks to travel and meet with constituents.

“[I can] dedicate a lot more time than other people who are supporting their families or working with full-time jobs and stuff like that,” she said.

“It’s great, but in the beginning, it didn’t really work so much to our advantage in the sense of being able to acknowledge that we are also our own people living our own lives and we can’t dedicate all our time to this cause.”

‘There are problems with the structure – it is hard to be in this as an everyday person’

Ducasse-Singer said travel costs have been another significant issue.

Voice members are entitled to a travel allowance if they need to travel more than 40 kilometres for an official meeting. The allowance, the state government says, reimburses elected members for “the cheapest form of travel” as well as accommodation and meals.

But Ducasse-Singer said Voice members have still had to shoulder out-of-pocket costs.

“I feel like the government could definitely offer us more, but so far we manage how we are,” she said.

“A lot of us from my region have gotten help from external organisations within our own communities to help with fuel order vouchers here or there, or some other organisations have been really great to provide cars… and stuff like that.”

‘It is a lot to ask of community leaders who are already taking on lots of extra duties outside of their paid work anyway’

Like other elected members, Ducasse-Singer believes the Voice’s administrative wing, the Voice Secretariat, needs more resources.

The Voice Secretariat sits within the Attorney-General’s Department and its subprogram of Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation, which has a budget of around $14.6 million in 2024-25. Within that, the Voice is allocated $715,000.

The secretariat has six staff comprising a director and five policy officers.

By comparison, the Premier’s Delivery Unit, the controversial body headed up by Labor-connected public servant Rik Morris overseeing progress on the Malinauskas Government’s election commitments, has seven full time equivalent staff and a $2 million budget.

“It is a small, lean and very dedicated team in the secretariat,” Aboriginal Affairs Minister Kyam Maher said last month.

The secretariat supports the State and Local Voices through policy advice and “project-based and administrative support”, a state government spokesperson said.

Two policy officers are assigned to support three local Voices, they said, while the remaining three officers support the other three local Voices.

The inaugural director of the secretariat, Andrea Mason, resigned earlier this year reportedly to move to the North Territory for family reasons. The spokesperson said Mason attended all State and Local Voice meetings in 2024.

Maher has indicated the state government is open to making changes to the secretariat if necessary.

“How it works administratively, how the legislation works, I’m sure is going to be subject to change as we develop this model,” he said.

“That is something we are keen to understand [and] keen to look at as we go to the next elections in 2026 – any changes we need to make including… how the Voice themselves are renumerated but also how the Voices are supported.”

The state government’s overall commitment to the Voice, according to a media release distributed last year, is $6.1 million over four years – roughly $1.5 million annually. That’s not including the more than $4 million budgeted for the Electoral Commission to run the first and second Voice elections.

The hardest nut to crack

There was broad agreement among the Voice members InDaily spoke to that while more funding is needed, making Voice members full-time representatives is unlikely – and perhaps not even desirable.

Local Voice members are paid $3000 a year plus $206 per meeting attended. State Voice members receive a bit more – $10,500 plus meeting fees – while the two State Voice presiding members get $18,000 each.

“We are not, as some have suggested, doing this for the money,” Leeroy Bilney told MPs last month.

By law, Local Voice members are responsible for talking to constituents and discussing those views with fellow Local Voice members. They are also responsible for working with government departments, councils and other organisations on policies and procedures that affect their constituents and local region.

Keenan Smith is a cultural heritage adviser with electricity transmission company ElectraNet and a West and West Coast Voice representative.

The region Smith represents includes the Aboriginal communities of Koonibba, Yalata and Oak Valley in an electorate that stretches from Cowell on the eastern Eyre Peninsula to the Western Australian border. The West Coast Voice has so far held three meetings – two in Port Lincoln and one in Ceduna.

‘We had an expectation of hope and of getting something kind of different done within state government that hadn’t been done before.’

Smith, asked how they balance their existing work commitments with the new role, said: “I don’t think that was carefully considered when they were designing the Voice and what it would look like.”

“Because unless you work for state government – there are arrangements that they can do to facilitate you going to these meetings – but if you don’t have a job or you work in an area outside of government, it does make it quite tricky,” Smith said, while noting that participating in meetings online is permitted.

Smith, who identifies as gay and non-binary, has an arrangement with their employer to use leave entitlements to attend meetings but said “that’s not often the reality for others”.

“For those that aren’t employed… depending on where they have to travel and stuff like that, that can add another hurdle to them being able to participate,” Smith said.

Dr Anna Olijnyk, senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide’s law school and a close observer of the Voice’s structure, said the time constraints on Voice members “might be emerging as the most difficult nut to crack”.

“It is a lot to ask of community leaders who are already taking on lots of extra duties outside of their paid work anyway,” she said.

“If you’re not resourcing people to be spending a lot of time renumerated on an institution, they may not have the time to put into it.

“But the flip side is that the Voice is supposed to be an institution that gathers the views of communities, and so it makes sense for its members to be people who are very active members of those communities who do perhaps hold full time roles.”

Expectations vs reality

For 30 years, Scott Wilson has worked for South Australia’s Aboriginal Drug and Alcohol Council, the state’s peak body for Aboriginal drug and alcohol services.

He was elected to the Central Voice with 25 first preference votes and is a firm believer in the Voice model, stressing that “anything new is going to have teething problems”.

“At the end of the day, they had to start from scratch because there’s nothing in place before,” Wilson said.

“It’d take a little while to argy bargy to work it out what it is we can collectively put forward and what’s not on the table.”

Wilson suggested there may have been misguided expectations among some Voice candidates about the Voice’s functions, namely that it could advocate for specific service provision like, say, more childcare services in northern suburbs.

“But when we came together, obviously they were told this is what the Act and the legislation is about,” Wilson said.

“I think that perhaps people who nominated might not have fully understood that the Voice is there to provide input and advice around government legislation as it might or might not have an impact on Indigenous folk.”

Wilson said there are other avenues to advocate for service provision, namely the South Australian Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation Network (SAACON), of which he is lead convenor.

Differentiating the Voice’s role from existing Aboriginal organisations has been a key concern for Smith, from the West Coast Voice, who worries the Voice’s current structure may be “adding another layer of what’s already happening in the community”.

“I would like to see a way where we can kind of leverage the potential benefits from the Voice with working with the key organisations and people in our communities, as opposed to us being another layer of going out, getting advice and feeding back what’s already been fed back to other state bodies and federal bodies,” Smith said.

“I don’t think we had an expectation of what it was going to be, but we had an expectation of hope and of getting something kind of different done within state government that hadn’t been done before.”

Smith intends to remain on the Voice until the next elections in March 2026.

“We’ve still got another year to really kind of nut out further what this is going to look like,” they said.

“I don’t necessarily agree with some things on the Voice, but I still believe in its potential to do good for our communities.

“I just think that there needs to be more flexibility for us as Voice members and our communities to have more control of how the Voice works.”

‘Give us a chance’

Barring an extraordinary turn of events, the Voice’s future is secure as long as the Malinauskas Government is in power. Labor’s current political fortunes suggest this will be until at least 2030, at which time the Voice will be, advocates argue, a more established institution.

Advocates also say the political criticism prompted by the three resignations from the Voice was unfair, pointing out that an equal number of Liberal Party MPs have resigned from the Lower House since the last state election.

“If we’d been around for, let’s say, a four-year period and we were getting resignations, well then fair enough, maybe they could be critical,” Scott Wilson from Central Voice said.

“But they have the same problems where politicians are resigning… well before their terms are up – they just go through normal processes and have a by-election.

“I think that the whole concept of the Voice is a great idea and… once you’ve been around for a while it’ll just become part and parcel of the South Australian political landscape.”

Those involved in the Voice say they have a lot to be proud of too.

In his inaugural address to parliament, Leeroy Bilney noted there have been 18 Local Voice meetings – three in each region – and the State Voice has already met with state cabinet and department CEOs.

He also said the Voice has contributed to four bills. This includes the government’s Preventive Health Act and Office for Early Childhood Development legislation, both of which passed parliament late this year.

The government said the Voice’s contribution to the latter prompted a series of amendments ensuring that when the Office for Early Childhood establishes a committee, it needs at least one Aboriginal member. The definition of an “Aboriginal child” was also revised to include a reference to an “Aboriginal person”, reflecting the Voice’s view that “the importance of recognising family and community should be included in the legislation”.

Last month, Premier Peter Malinauskas praised the Voice for its “thoughtful, pragmatic engagement” with the government in its first year and said the Voice’s contribution to legislation “suggests this is something which has a practical meaning without infringing on anyone else in the community”.

But whether elected Voice members can sell the value of their work back to their constituents is another question entirely.

Back at Tiraapendi Wodli, Deb Moyle is regularly confronted with confusion about the Voice’s role.

“[I’m] fortunate having so many Aboriginal community members walk in the door – I hear firsthand… what community members are saying about Voice,” she said.

“Aboriginal community are just as confused as the wider non-Aboriginal community of what Voice is.

“What I sell my community is they’re not going to see the outcomes from the Voices, they’re going to see the outcomes when a future bill or legislation or policy is implemented and it has those cultural nuances attached to it.

“That’s when the department system is going to be better.”

More than anything, Moyle stresses that the Voice “needs to be afforded the time to show what is going to work and what isn’t going to work”. Other members agree.

“This has never happened in Australia before,” Dharma Ducasse-Singer from the Far North Voice said.

“And with the national vote of Yes failing, South Australia is starting it from the ground up.

“You have to give us the opportunity and give us the time and give us a chance.”